One day in Rain City, not too long after I found my first place to live as an independent person, I went into a second hand shop on K Road, just down from the junction with Great North Road, and there bought two items. The first was a Smith Corona portable typewriter in a beige travelling case; the second, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. The typewriter, which I no longer have, cost $30.00; the Shakespeare, which is still with me, rather less, but I no longer recall exactly how much. It is printed on onion skin paper and bound between faded red boards, with Shakespeare in gold lettering on the front; first published in 1905 by the Oxford University Press, this copy is a 1947 reprint. There are inscriptions on the flyleaf: For the Dawn in blue ink; and, below that, in pencil and in a different hand 4’ April 195. / from / Mrs Devoro (Gran). I have written my own name in adolescent script above the first inscription. This book has 1166 pages and includes the plays, the sonnets, the poems, along with a preface, indices of characters and first lines of songs, a glossary; and still seems to me a miracle of rare delight. As for the typewriter, it’s more mystery than miracle: what did I use it for, when did I sell it, where is it now? I know I bought it because I wanted to be a writer so I suppose some of the pieces I still have copies of must have been typed upon it: pica not courier, though I did not know of that distinction then. I almost remember the shop, sparse, unassuming, generic in those far-off unsophisticated times. A place where a young student could find two unassailable guides and with them begin upon a path of dreams.

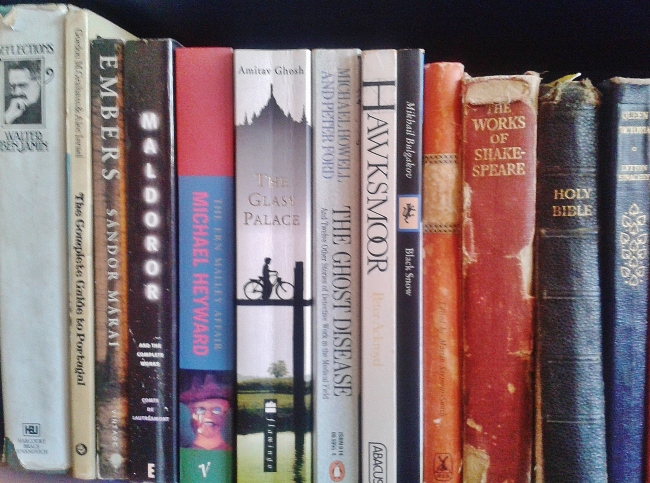

If the Shakespeare was my first second hand book, it wasn’t my last. Over the years, and increasingly, I have found my recreational reading among the bizarre eclectics of junk shop shelves. This is not only because I’m cheap; I like the way you find oddities among the random assemblies in such shops and in some respects prefer the choices thrown up in such places to those available in bona fide bookshops; which, frequently if not universally, tend to have a relationship with current fashion. Whereas the books you find in second hand shops either have no relationship to fashion, or a negative one: they are books people bought or were given by mistake, never wanted in the first place, don’t want any more; many, from deceased estates, are in the ultimate sense abandoned. I’ve never inventoried my library according to any criteria but it’s possible that half, perhaps more than half, the books I own once belonged to somebody else: among them favourites like my Plutarch, my King James Bible, my Shakespeare, my Rubáiyát, my Ulysses . . . and now, as I look around, I realise that not just the books but the shelves that hold them, the desk I work at, the bed I sleep in, the clothes I wear, the pots and pans I cook with, the plates I eat off, the cutlery I use, the glasses I drink from all came to me from some known or unknown previous owner. The only exceptions are the pictures on my walls, which include some originals, and appliances like this computer, the stereo, my mobile phone: items which take such an individual imprint that you would not want someone else to have used them first. One effect of this second hand life is that you feel surrounded by ghosts, not so much from your personal past as from the past of the objects themselves. It is therefore important that you like the things you buy or otherwise acquire; and I have on occasion refused to purchase, refused to accept, desirable objects because I was suspicious of their provenance. In other words I did not want their ghosts in my life. As for those I have allowed to live with me, they are myriad, a throng, a multitude who nevertheless seem content to exist mostly in mute abeyance. And yet there are moments, in dreams perhaps, or in the reflections arising from the reading of a book, or just in the course of an ordinary afternoon—when golden light shines through the opulent grime of the window panes—in which these presences declare themselves in all their richness and strangeness, their mysterious familiarity.

Ghosts are of course about us all the time; never more so than when we are in the city, which is the home of the dead as much as of the living. On any urban street we walk down they are with us, a horde, an army, a host, all those defunct souls who once walked these streets themselves and are now undone and yet not gone. I hear their voices when I go up to the wine shop or to the tobacconist, the whispering ghosts who once took this very same path for the very same reasons that I do now; and exist, if that is the word, in a state of suspended desire, of unconsummated, indeed unconsummatible, yearning. You cannot help but listen but to respond to the importunities of that grey murmuring mass is to mistake your way; or worse, to lose it altogether. If, without stopping your ears, you can resist their siren songs; if you do not pour for them libations of black blood to drink; if you make your way forthright and undismayed into the admittedly fading light, they will fall back, as they must, those dead, before the single imperative of the living: our futurity.

To walk in a city is also to enter a forest of signs; these days that is true of any town on the globe. Even in the 1950s, in the small, remote village where I grew up, there were signs: at the end of our street, on the wooden walls of a two-storey double-fronted verandah-ed building that was a remnant of the original business district, destroyed by fire in 1917, there were pale hieroglyphs: the blue of an advertisement for Bushells Tea, the red of another for Craven A cigarettes; which my father, in a direct confirmation of the intelligence of signs, smoked while he drank his cup of tea. Further on, as you walked up towards Clyde Street, you would see, at the telephone exchange next to the Post Office, through a big plate glass window, the operator plugging and unplugging the robust rubber sheathed cables with their heavy, shiny protuberant steel points which she, like the conscience of the town, used to connect and disconnect people on the party lines. Then the shop fronts, the grocer, the draper, the news agent who sold toys and books: even as a ten year old I was a flâneur, idling among signs, reading their legends, deriving from them an inchoate map of my time and place which I used for nothing except further navigation. I don’t think people then wore signs on their clothes the way we do now; or only when they trotted onto the field or the court to play football or basketball. Now we are like motile signs ourselves, abroad in the forest of signs that is the city. Sometimes, beneath the railway bridge for instance, you see posters peeling from the hoardings, and beneath them posters of previous entertainments peeling, revealing advertisements for even more antiquated entertainments below: an inches thick archaeology of the ephemeral, city as palimpsest, its signs imperfectly erased and then written across, again and again—for whom? Who reads us? Who scries the whole of this random assemblage? What is it for? Some forgetful god, perhaps, would see our totality; if s/he were not so concerned with events in the Andromeda Galaxy. As it is we are like fragments of words from a great sentence that is always being spoken yet goes unrecorded; vocables in a cry made out of our own yearning; isolate leaves falling from language trees in the forest of signs.

The random assemblages you find in second-hand shops—curiosity shops, junk shops, opportunity shops—are analogous to the larger assemblages we find across city streets. Authored by no known hand, the forest of signs yet seems to imply some coherent, if hidden, text; whereas, in a second-hand shop, hasn’t some individual selected what we see before us? Isn’t there some intention? Well, yes and no: selection is probably less the point than mere assembly; and the intention, as with so many of the signs we see abroad in the city, is not to make some statement, imaginative or otherwise; it’s simply to attract a buyer, to invite, provoke, solicit, a purchase or a sale: isn’t it? Any coherence that we might find in such places comes only as a by-product of this commercial imperative; and we understand that these days in our bones. Nevertheless something else is going on as we trawl the streets of the city or go, as we call it, op-shopping: we are like a bricolage artist, constructing from random materials an order that satisfies our own sense of things; a mosaic maker, picking out shards of faience or glass or tile and putting them together to construct an image that carries a meaning, even if that meaning belongs only to one person, who may not themself fully apprehend it. This also mimics the way we use the language that is our common inheritance: we choose from the historical store of words those which make sentences that tell the world who we are, how we feel, what we will and won’t do, our loves and hates. This is so like the processes by which art is made that it must either be that we are all artists of some kind or else that the bases of art lie in an understanding of the world as a democratic space in which there is room for each of us to make signatures to tell our fellows who we are. So it is that out of those random assemblages, put before us with such unthought generosity, we are free to pick and choose, take or leave; and so make a small story of an hour, a day, a life. Furthermore, whatever among these things we leave behind when we pass on can themselves be taken up by other hands and turned to other uses; re-configured in other lives. And in that sense, albeit anonymously, we attain a kind of immortality.

Some years ago, when I still had ambitions to be a screen writer, someone gave me a second hand copy of a book called Johnny Rapana by an author called Charles Francis. It is an accomplished, unpretentious novel set between a small town and Rain City in the 1960s; and tells the tale of the eponymous hero’s trip to the metropolis, the disasters that befall him there, his tragic alienation from the community from whence he came. I thought it would make a good film but the proposal I wrote found no favour, perhaps because it was suffused with nostalgia for that then unfashionable decade. Francis, an Englishman by birth, lived an itinerant life, working in shearing sheds, as a musterer, drover, horse-breaker, show-jumper, tree-feller and taxi-driver; the detail of country life in his writing is exemplary. He published two other books: The Big One, set amongst crocodile hunters in the Northern Territory during the contact period; and a detective story called Ask the River which unfolds in one of my old home towns. This was such a good title, and my disappointment over Johnny Rapana so great, that I at once decided, on no good evidence, that I would adapt this other book to make a script for the period film I wanted to write. These were pre-Amazon, pre-internet days; you had physically, like a private eye, to hunt down such things for yourself. Over a period of years, then, in any junk shop anywhere I was, I scanned the dusty shelves hopefully for a copy; in second hand bookshops between here and Luz I asked at the counter for Ask The River. This quest quickly took on an absurdist aspect; while I found many copies of Johnny Rapana, and once a copy of The Big One (which, stupidly, I did not buy), no-one knew anything about Ask The River. In my paranoia I began to think that people thought I was making it up; sometimes I wondered if I had. And then, one day, in Smith’s Bookshop on Manchester Street, I found it: a red hardback, lacking a dusk jacket, but the veritable volume; published 1964, the same year as Johnny Rapana, by the same publisher, Whitcombe and Tombs. I bought it for $3.50 and bore it off in triumph; hardly daring to read it; already envisioning the film locations: mist wisping from the river on a winter morning, the clank of hidden coal trucks on the railway bridge, muffled voices, a mysterious splash, a car engine accelerating away as the bodies wrapped in a candlewick bedspread, secured with number 8 wire wrapped round a trailer axle, sink into the brown water. Who would have thought? The book has many faults—confused plotting, over-writing, stock characters, a ridiculous denouement—but that wasn’t really the problem. Improbably, indeed inexplicably, it had been overtaken by events and was impossible not to read as an inadvertent, mixed up prophecy of the veritable murders of a farming couple called Crewe in the district of that town in 1970; about which a film had already been made. I was so disheartened I felt sick; obtuse in my weird obsession, strange in my pursuit of the future in the past; deluded. But now, years later, I wonder—perhaps there is a story here after all. The tale, not of a small town murder and the city cop who hunts the killer down; but of someone in pursuit of a delusive object who nevertheless uncovers precious knowledge: how to be, not what he wants to be, but who he is; how to tell the difference between real and imaginary questions; how, in truth, to ask the river.

Like many people I have a fantasy that one day in a second hand shop I will find a dusty old painting that is worth—millions? No, for me it’s more about ownership than money, if I was lucky enough to find an original watercolour in good nick by Vaughan Sheridan, for instance, I certainly wouldn’t sell it; or a humble, probably disintegrating, Philip Haines drawing; an unknown Howard Hodgkin. I once tried to make a story out of this obsession, inventing a painter by the name of Jakob Oort and finding in a second hand shop in Petersham one of his lost works. Jakob disappeared in the late 1970s, was thought to have died but the discovery of this painting, Sedna’s Chair (1984), suggested otherwise. I bought it for $75.00 from the old Chinese woman who spent her days knitting and talking in Mandarin to her cat, had it cleaned and restored, went searching for its provenance and its antecedents. That took me down to a settlement—by now I was living in the Emerald City—with the improbable name of Aphrodisiac Junction, a real place as it turned out, one of those unauthorised suburbs, a Happy Valley or a Tinpot Town, where marginal types gathered until the municipal authorities erased their illegitimate domiciles from the landscape. Here I came across Jakob’s lover, Sedna, and her daughter Serein; but then the trail went cold. This story became so vivid in my mind that I suffered real distress when the second hand shop in Petersham closed: never again would I take the path from the door, past the bookshelves, up two steps to the left, down a passage to the right, down another passage, again to the right, which brought you back to a view of the entrance that you could not now reach because of the things stacked high and precariously in the centre of the room. The old woman’s prices were extravagant, unaccountably so, since it seemed unlikely that anyone would pay, for example, the three hundred dollars she was asking for a large fat peeling plaster Buddha with a vaguely salacious leer sitting upon an old bentwood chair which was itself placed on top of a curiously shaped corner bookshelf next to a desolate, 1950s standard lamp with a broken yellow shade and an ashtray set into the small round Formica table halfway up the shaft; nor buy, for $40.00 each, the cat’s kittens after she birthed four black and white ones and used to lie purring, suckling and grooming them, in the shop window next to the clay pigeons, the bottles and the jars, the cantor dust. I did buy there once a copy of Terra Amata, an early work by French-Mauritian writer J M G Le Clézio who, in 2008, to everyone’s surprise, including his own, won the Nobel Prize for literature; also a couple of alarmingly realistic metal scorpions that I keep on a bookshelf in front of my multiple copies of Les Fleurs du Mal and next to the full length mirror and the red armchair; and, finally, the idea of Jakob Oort himself, whose biography I might yet write, whose works, although they are imaginary, I still look out for—and may, fantastically, one day even find.

There should be a tense called the present in the past: yesterday, in a second hand shop on Carlton Crescent I bought a copy of the catalogue for a show that visited these shores last century—Gold of the Pharaohs. A strangely resonant moment. My mother, twenty years ago, gave me a small booklet of postcards that I now realise were part of the marketing for this show. There were about thirty of them and you could tear them one by one from the booklet and send them off to people. I held onto them for as long as I could; as if they were protective amulets of the kind worn by the priests and scribes, the kings and queens, illustrated therein; but most of them have gone now and nor can I find the remnant among my things. Perhaps tomb robbers have been here too. In the catalogue, however, these images return, as if from the beyond: the Cube Statue of Hor, for instance; the Statuette Usurped by the High Priest of Amun; the painted wooden Shabti Box of Maatkare. In itself I suppose this catalogue is not worth much; I paid a few dollars for it and you can pick them up online for a little more than that; on the other hand it is a marvel. Much of the material therein is from a series of intact or nearly intact tombs found at Tanis in the Nile Delta and excavated by French archaeologist Pierre Montet in the 1930s and 40s. These were the burial places of people of the Third Intermediate Period, that is, from about three thousand years ago or the time of King Solomon, whichever you prefer. The wonder is that, through the medium of a book, found accidently, randomly, I come as close as I am able to possession of these fabulous artefacts; and that, from beyond the grave, I feel my mother’s hand in the gift. Images are of course not actual; but try telling the Egyptians that. To them a picture was the thing it depicted; just as the mere speaking of a name guaranteed that person’s continuing existence in eternity: were they wrong? I find most poignant the shabti, tiny figures of workers, with their hoes, picks and baskets, that were placed in tombs to do the work for the deceased in the afterlife: to plough the fields, to fill the channels with water, to carry sand from the East to the West. An important corpse would have 365 of them, one for each day of the year; and alongside them 36 kilted overseers with whips in their hands, one for every ten workers, to ensure swift completion of their appointed tasks.

A wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, was a veritable thing, a room in which marvels—animal, mineral, vegetable, fictional or otherwise—were assembled: everything from a unicorn’s horn to Montezuma’s crown, from ambergris to zebra hide. They were a theatre of the world, an encyclopaedia in which real objects, standing for themselves, replaced written entries. Of course they were exclusive, the province of the very wealthy, and in our time have been succeeded by museum collections into which anyone may go; but the vast assemblage of the material world cannot now be, if it ever could, contained in one place; and anyway so much of what we make these days is ephemeral, without any pretension to longevity, mere tat that serves to divert us for a moment from our real concerns, whatever they may be, before it passes away into the oblivion of the unremembered. Or is it? We live in a material world and while anyone can, if they wish, eschew possessions and all that is thereby implied, the rest of us will continue haphazardly to assemble our own wunderkammer and populate it howsoever: with Star Wars toys, perhaps, or posters of Elvis Presley movies; with second hand books or Jamaican 45s from the 1960s; Hello Kitty memorabilia or voodoo dolls; emu eggs or nutcrackers made after the design of Hawaiian wooden idols. And in this manner we make of our living spaces something between a museum and a tomb, with our future grave goods assembled around us. Most of us, if we are not monks or ascetics, are hoarders of some kind or other; often trawling online for treasures to add to our collections; whereas before the ubiquity of the internet the only option was to search through actual repositories: shops, markets, auctions and so forth. Both are random processes; but the former commonly seeks to identify the thing before it is found whereas with the latter it is the other way round: we don’t know what we will discover until we actually find it. I prefer the second option myself but no value judgment is implied; no rule need be observed nor protocol followed; amongst the limitless promiscuity of things of the world we may follow our inclinations wherever they may lead; just as we may compose and recompose, combine and recombine, howsoever we please, the ghost alphabet, the language of the streets, the forest of signs. Despite the mind-forged manacles of economics and the serial oppressions of politics and war, despite our insignificance and our obscurity, our virtual nonentity, we are not shabti, slaves condemned to labour for our dead masters through eternity; we are free.

Pingback: Second Hand Life | Jean Vengua